Lucky LOKI Man Survives Grand Mesa Thunderbird Avalanche. Still Inspired by the Ute Legend.

What Happened?

The author Seth Anderson climbed the Grand Mesa Thunderbird Couloir. He and Ann Driggers director of Grand Junction Economic Partnership made the first known descent on skis March 17, 2010. Unfortunately, most of Anderson's trip down the steep mountain was face first sans skis wrapped in an avalanche. It might be the only chance in decades to ski the Grand Mesa Thunderbird. The legend and existence of the Thunderbird Couloir was my life-long passion which no one else seemed to share.

decades to ski the Grand Mesa Thunderbird. The legend and existence of the Thunderbird Couloir was my life-long passion which no one else seemed to share.I've looked up at the natural formation with wonder before I knew its name. I longed to view, hike, and perhaps even ski it up close.

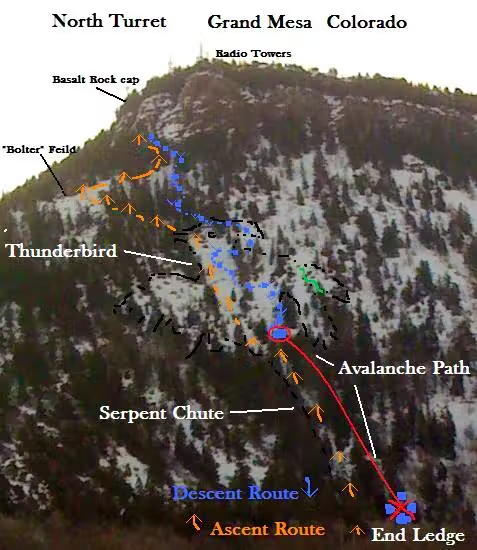

The Grand Mesa is not a mountaineer's typical query, but the North Turret has merit — if not for rugged shape and local proximity, then for the Ute's legend of the terrifying Thunderbird story played out in hieroglyphic form on its steep slopes. The local Utes believed the light-colored shale appeared as a wing-spread Thunderbird grabbing a long skinny serpent-like chute rarely visible from below. When a coming storm's light shows the Thunderbird grab the Serpent, it rains in the valley. I have witnessed this just once in 1992.

My brother, Dirk, and I scrambled up the Thunderbird route in September 2009 and found it enjoyable but a “bushwacky” climb above and below. Having an indomitable thirst for intriguing and hard-won ski routes, Ann Driggers, president and CEO of the Grand Junction Economic Partnership, was fired up to go after years of me mentioning it.

Ann and I left Rapid Creek Trailhead at 5 a.m. March 17, 2010. Hiking the dark road till snow coverage at about 6,000-feet elevation required flotation. We put skins on our ski bases and schussed upward crossing a meadow and entering thick low-slung brambles. The sun broke on the glowing Bookcliffs below as we bobbed and weaved through snags of oak brush. We stepped onward to the bottom of the narrow Serpent Chute.

We fixed skis to our packs crawling and kick-stepping up the barely covered Serpent Chute to the wider Thunderbird Couloir above. Reaching the crest, we paused for a break. We decided the west-facing Couloir had not had enough sun to soften it from its hardened state. We skinned steeply toward the basalt-capped summit. I spied a possible scrambling route to try at a later date. We beamed from the great mountain climbing experience we had enjoyed that is within view and reach of our homes.

At about 11:30 a.m., Ann and I skied down to the head of the great bird. I followed Ann “skiers left” out onto the sharp beak. We skied to center, then left again on mostly icy snow. I decided to ski back into the Serpent's gullet. I dropped over a rocky knoll into an open snow patch. The rough textured snow cracked, rumbled and dialed open like a 3-D puzzle.

“No! Stop, Ann!” I yelled behind me. I tried to force a turn to get out of the slide but was immediately sucked under the snow.

I was screaming face down, snow chunks and loose powder surrounded my entire being. It was exactly as I had envisioned being in an avalanche, only rougher. I saw myself sliding quickly to my burial, suffocating and freezing solid in cement-like snow.

I tried to swim and kick to the surface and get my feet pointed down. The snow pounded my face to the rock and debris. I persisted — just as the slide caught air I was freed to put my now ski-less backcountry boots below me.

I was surrounded by snow and launched off of an abrupt drop. I hit hard and my legs crumpled. The thickened snow slammed me without pause and bludgeoned me blindly through hard trees and over two smaller drops. The trees grew denser. I was spit out and slid in slow motion onto a sloping ledge. I clung to a slender tree suspending me above another 80-foot drop.

I was relieved not to be buried and able to breathe. I was horrified when my legs did not move with my body. I was in shock and yelled for Ann to find me. “Are you OK, Seth!?” she shouted back. “I'm HERE!” I replied.

Blood dribbled past my eyes onto my phone as I dialed 911. “I am on the west face of Grand Mesa on the north side of Rapid Creek just above Palisade. I've just been in an avalanche triggered fall on the Thunderbird Couloir,” I said trying to stay calm. I vaguely recall the responder: “Thunder-what? You're kind of breaking up, sir...”

Ann skied up next to me on the ledge, “Oh my God, Seth, are you OK?” I repositioned my crushed legs uphill to slow my bleeding and handed her my phone. My cell phone signal was gone so Ann managed the rescue effort with calming strength.

Just after 1 p.m. Ann called 9-1-1 and coordinated with Mesa County Search and Rescue and Powderhorn Ski Patrol's Rondo Beucheler. Rondo is also the owner of Palisade's Rapid Creek Cycles and knows the area better than most.

My pack and skis were gone, only my uninsulated Loki shell covered me as I shivered immobile, contemplating the blood once soft inside my legs now stiffening into huge and painful trunks to compensate for lack of solid bone structure. I suggested that I should wrap a belt tightly at least around my left leg which was broken at the femur and swelling more dramatically. Rondo insisted not to try it if I wasn't bleeding through. Ann handed me her light down jacket as she improved a platform and prepared the rescuers.

Around 4 p.m., St. Mary's Care Flight helicopter blades pounded the air and searched for a safe place to land below us. Pilot Bill Reed landed Search and Rescue's Jose Iglesias, Joanne Black and flight nurses Tom Feller and Rob Klimek to climb up to our ledge. They set up IV fluid and painkillers to essentially save me. By now the shock had worn off and I was in serious, sometimes vocal pain. I was elated to have Sanadam, Rich Moody, Bob Marquis, Terry and many more search and rescue members be so calming and strong. They made me want to live beyond the delicate thoughts of my new son, Asa, and loving family. The IV fluid was my nemesis. I wanted water to moisten my throat so bad but I was only allowed to eat snow. Sensible for surgery... I wasn't sure I could hold together for the hospital.

Many more well spirited and strong search and rescue members arrived to help. I was soon strapped to a rescue basket and rappelled down the initial drop. We trudged across several more stepped slopes to one more rope lowering to the waiting helicopter.

Flight to Recovery

By sunset I was delivered via rooftop landing to talented hands and openly kind souls in the new tower at St. Mary's. Dr. Hilty, Dr. Narrod and Dr. Dolecki made lasting artwork of my near fatal condition. I was saved by technology and intelligence and yet nearly as much by the pure love I have received during my rescue and continuing recovery. I am eternally grateful for more than I could ever repay in my lifetime. It is as if I needed death in my face to realize how many great people I would miss and be letting down.As I lay reviving two severely broken legs in a St. Mary's patient room, part of a message from Sister Jane McConnell appears:

“To all who are sick or injured let them know that they are loved and held in YOUR careful embrace.”